Hurricane Ida makes a mockery of big oil’s philanthropy

During Hurricane Ida, energy companies briefly paused efforts to claim credit for combating the problems they’ve caused.

AS HURRICANE IDA wrought destruction throughout Louisiana and Mississippi this week, the companies that own the oil rigs and refineries in the storm’s path — and helped fuel this and the other natural disasters now upending life in every region of the world — said very little. While a highway collapsed, people died, homes flooded, power grids shattered, and more than 1 million homes and businesses lost power, the Twitter feeds of Exxon Mobil, Marathon Oil, Valero, Phillips 66, Chevron, and Shell remained notably inactive.

That silence contrasts with the steady patter of positive PR the big oil and gas companies usually spout about their roles as stewards of the environment. Ida — whose power stemmed from the unusually warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico, turning it into the “poster child” for climate change-driven disasters — made Big Oil’s usual pledges to help us cope with the climate crisis ring impossibly hollow.

Just weeks before the hurricane, Exxon, which manufactured doubt about climate change for decades despite knowing that its production of fossil fuels was causing the crisis, tweeted about its support for the Paris Agreement. Shell bragged about its support for wind technology, even though the vast majority of the company’s business is still oil and petrochemical production, and it is on track to still be producing 1 million barrels a day in 2050. Chevron pledged to advance a low-carbon future and invest $750 million in renewables and offsets by 2028, while spending far more fighting an attorney who won a judgment against the company over the environmental harm from oil extraction in Ecuador. And Valero boasted about giving away 500 trees near its refinery in Meraux, Louisiana — a plant that has violated the Clean Air Act.

Such greenwashing — or perhaps false advertising — is par for the course for big energy companies, according to Karen Sokol, a professor at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law. “They frame themselves not as a major source of the problem, but instead a key part of the solution,” said Sokol, who was reached in New Orleans, where she and other residents have no electricity. “That’s nuts, but so far it has been well received by policymakers, even inside the Biden administration as well as some environmental groups.”

To be fair, the energy companies have had a lot to focus on — and perhaps little time to tweet — over the past few days. Hurricane Ida forced the partial or full closure of many oil rigs and refineries, and companies have had to evacuate workers and cope with rising waters and intense winds that can trigger leaks, spills, and flares. “Our focus is on employees and their families,” Ola Morten Aanestad, a spokesperson for Equinor ASA, which owns and operates an offshore oil production platform in the Gulf of Mexico, wrote to The Intercept.

Everyone else in the area is in crisis mode too — something that’s become routine in recent years. “We’re entering a new phase of climate change now where we see climate related disasters on a daily or weekly basis,” said Bill Ripple, a professor of ecology at Oregon State University. Ripple’s most recent report found that records have recently been set in 18 of 31 critical planetary measures, including levels of melting ice, greenhouse gases, ocean changes, and temperature. “We are in an emergency that humanity has never seen before. We’re looking at unfathomable changes and impacts to society.”

Claiming Credit for Combating the Crisis They Caused

Most of the time, the fact that fossil fuel companies are causing these cataclysmic changes doesn’t stop them from claiming credit for combating them. After an unprecedented storm froze most of Texas in February, an occurrence that clearly stemmed from the warming of the Arctic, oil and gas shippers from Phillips 66 and other companies set out to save the sea turtles in the unusually cold waters — and then to memorialize their acts of environmental heroism on company’s website, which deemed the rescue “a great day for more than 2,000 green sea turtles.” Phillips 66 heralded the crew’s efforts without noting the irony that the turtle-savers had, on balance, done more to harm than help the creatures.

Big Oil’s assistance to the human victims of climate disasters also appears absurd and insulting given the industry’s responsibility for the crisis. Energy companies’ donations to the communities that suffer most from climate change and the other environmental harms oil production causes are particularly paltry when considering both the true costs of the destruction and the great wealth they have amassed extracting resources from those areas.

PBF Energy’s Chalmette Refining in Louisiana touts a $150,000 contribution it made to the St. Bernard Parish government to help fund redevelopment of Bluebird Park, which has been heavily damaged from previous hurricanes. Marathon Petroleum is the largest fundraiser for United Way in St. John the Baptist Parish, Louisiana, according to the company’s website. St. John, which is home to the census tract with the highest risk of cancer from air pollution in the country, is a short drive east from the company’s refinery in Garyville and has suffered major damage and flooding from Ida. Marathon, which is valued at more than $28 billion, gave over $300,000 to the charitable organization, which provides food, water, and toilet paper to locals during hurricanes.

In Houston, where temperatures regularly reach into the 90s, Phillips 66 supplied volunteers who helped plant native trees at De Chaumes Elementary School to bring much-needed shade for the students. Last August, after Hurricane Laura, the Exxon Beaumont refinery along with another local company, Tri-Con, donated nearly 15,000 gallons of fuel to the Texas cities of Orange and Vinton, which were both hit hard by that storm. The gift garnered the company good will from the locals, according to the Exxon website, which quoted Orange Mayor Larry Spears as saying, “ExxonMobil’s support brings hope in this time of need.” In Vinton, where about a third of the population lives under the poverty line, Mayor Kenneth Stinson said, “It is heartwarming that ExxonMobil thought of us.”

Anne Rolfes, director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, a group that works in communities living near refineries and chemical plants, said that such oil industry philanthropy is aimed at the larger public rather than the people directly affected by their facilities. “Rich guys in big cities are their audience, not the people who are feeling the climate change impacts or the pollution,” she said.

“Rich guys in big cities are their audience, not the people who are feeling the climate change impacts or the pollution.”

It should be noted that Exxon also gave $500,000 — along with the company’s “thoughts and prayers” — to Gulf Coast communities in 2017 after Hurricane Harvey, a storm that caused an estimated $125 billion of damages. And, in late summer, Phillips 66 contributed $1 million to support hurricane and wildfire disaster relief efforts: a considerable sum compared to donations from other companies and yet a tiny fraction of an estimated $210 billion in damages caused by climate change last year. Those costs are expected to reach $1.9 trillion annually by 2021, if the warming continues unchecked.

Exxon, PBF Energy, Valero, Shell, and Phillips 66 did not respond to inquiries for this story. But on its website, Valero describes itself as “tirelessly focused on safety.” The company also prides itself on its “gumbo giveaway” event in Port Arthur, a town that has the largest concentration of oil refineries in the U.S. and an elevated cancer rate. The site also notes that “Valero strives to be a good neighbor and looks for opportunities to work directly with local officials and fence-line residents to improve the quality of life in its communities.” PBF Energy, which operates the Chalmette refinery, writes on its website that “safety is above priorities, it is a life value.” According to Shell’s website, “Shell’s top priority is to protect people, assets, nearby communities and the environment.” In addition to outlining its work on turtles and wetland protection, Phillips 66’s website says, “Our commitment to sustainability is based on operating excellence, environmental stewardship, social responsibility and financial performance led by rigorous governance. Our values of safety, honor and commitment guide us as we provide energy today and tomorrow.”

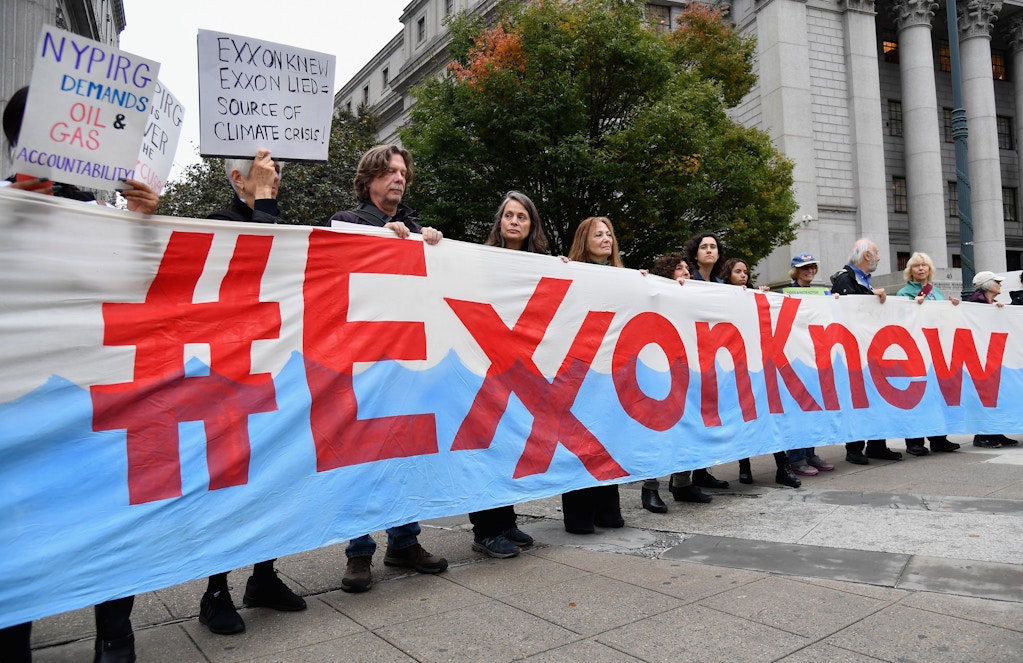

Climate activists protest on the first day of the Exxon Mobil trial outside the New York State Supreme Court building on Oct. 22, 2019, in New York City. Photo: Angela Weiss /AFP via Getty Images

Fighting Efforts to Extract the True Climate Costs

The problem isn’t the gifts from the oil industry, but the fact that they ease the way for companies to continue inflicting damage, according to Sokol. “Why is it funding these community projects? Why is it now not overtly denying climate change but instead positioning itself as a fossil fuel savior? So it can maintain its way of doing business,” she said. “They are working concertedly and have been for years on ensuring that they will be the ones dictating the sorts of policies that will be in place to respond when there was a concerted call for climate action.”

While Big Oil continues to make — and publicize — their philanthropic contributions, they are fighting legal efforts to collect on the true costs of the climate crisis. More than 20 cities, states, and localities, including Baltimore, have recently sued fossil fuel companies seeking compensation for the financial burdens now being shouldered by the public. Although those cases could help bring much-needed funds to suffering communities, Sokol insists that saving face — and the ability to keep producing fossil fuels — is more important to the oil industry than the money.

“Whatever it pays it could write off as a cost of doing business,” said Sokol. “Why the industry is fighting tooth and nail against these is it doesn’t want to lose its social license.”

So far none of these cases have reached the discovery stage. But if they do, Sokol believes that documents released through that legal process will be devastating for oil companies. “That’s one of the reasons the industry is so freaked out by these cases,” she said. “Once that starts happening, I believe it will completely unravel.”

In the meantime, Rolfes, of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, said that there are a few things she’d really like from the oil companies. “I want them to acknowledge that climate change is a real problem and that they’re fueling it — and stop pursuing fossil fuels,” said Rolfes, who was heading out with a generator, gas cans, tarps, food, and water to help people affected by the hurricane in St. James, Louisiana. “Every storm and every wildfire is a message that we need to take that action.”